Football is a game of continuous movement, the aim of which is to successfully progress the ball into the opposition’s defensive third to create a goalscoring opportunity that could be the difference between heartbreak and elation. In this article, we introduce the different types of movement to receive the ball and the relevant terminology that is used in the FIFA Football Language.

In order for an in-possession player to have an impact on the game, they must first be able to get on the ball in an effective area, usually by recognising the space in which to receive it and performing intelligent and subtle movements or high-intensity movements to get themselves into that space, depending on the game scenario. Players may also make movements that are designed to open up space for their team-mates to move into and receive the ball. The five types of movement covered in this article are in front, in between, in to out, out to in and in behind, with examples from the 2018 FIFA World Cup™ to showcase the different types of movement.

In front

The first movement we will look at is in-front movement. This occurs when a player makes a movement to receive the ball in front of the opposition’s first unit line, which can happen in any third of the pitch and either inside or outside the opposition team shape. A couple of examples of in-front movement are:

1) an advanced full-back dropping in front of the opposition’s wide player to receive a pass from the centre-back; or

2) a creative central midfielder moving to receive the ball in front of an opposition’s mid-block when the midfielder’s team are in possession and looking to penetrate the mid-block.

When analysing the 2018 FIFA World Cup, FIFA found that Spain made the most in-front movements to receive the ball, with an average of 156 per 90 minutes. This was 44 more than their closest competitor, Australia, who made 112. Interestingly, out of the four teams that made the semi-finals of the competition, only England finished in the top ten in terms of in-front movements made. Spain’s dominance in this area was further reinforced by the fact that three of their players featured among the top ten to make in-front movements. The reason for Spain being so well represented in this department could be due to the number of times opposition teams set up a mid-block or low block against them.

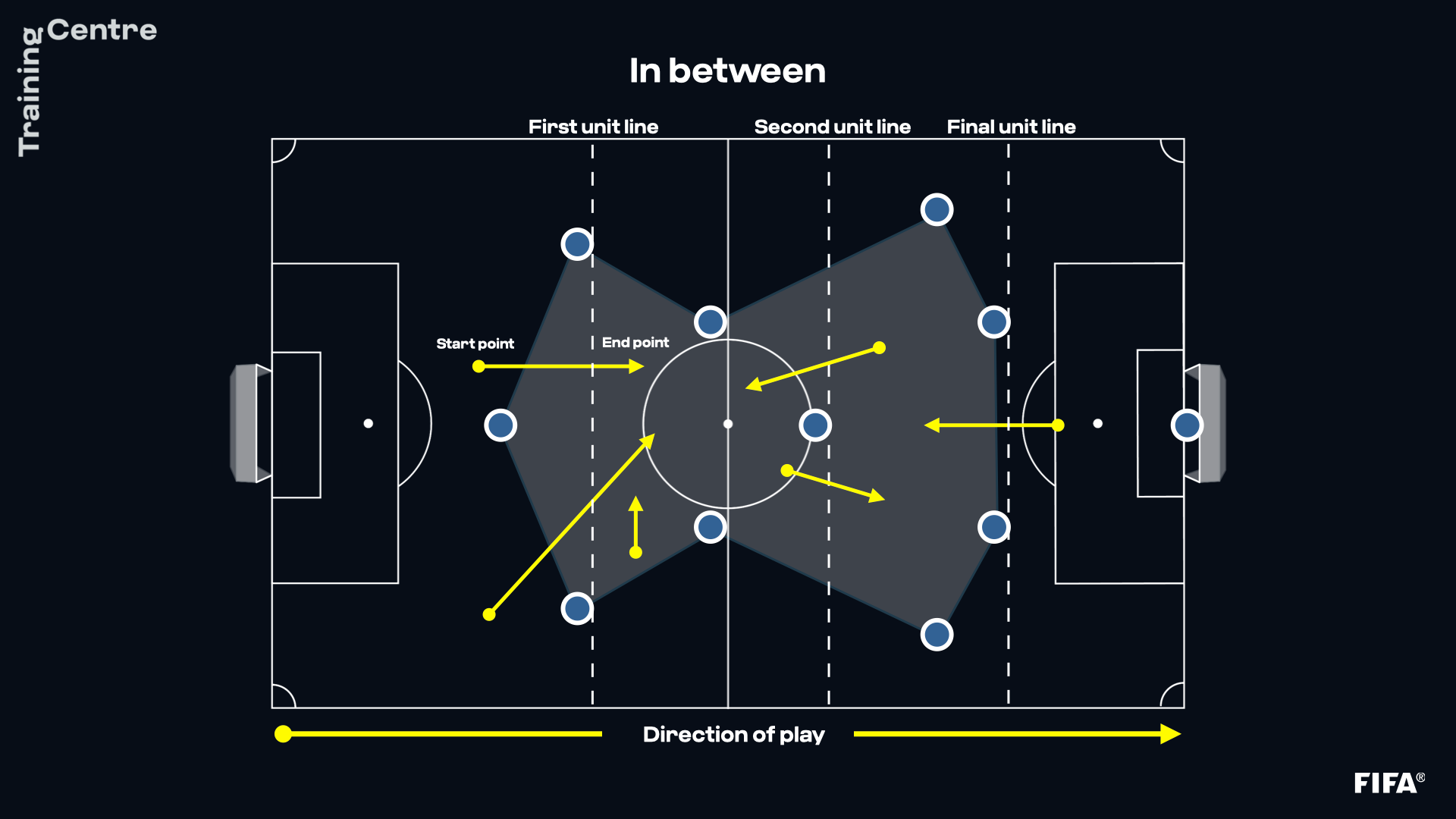

In between

The second type of movement within the FIFA Football Language is in-between movement. This occurs when a player makes a movement to receive the ball between two units, inside the opposition team shape. The phrase “inside the shape” is depicted in the shaded area of the image above. Teams most commonly play with three defensive units, in which case an in-between movement is made between the opposition’s midfield and attacking units or between their defensive and midfield units. The objective of this movement is to try to find space between the lines, thereby offering the in-possession player the time on the ball to pick out a team-mate with a penetrative pass or to progress the ball forward into a more threatening area. It is often the most creative players in a team that look to utilise this kind of movement to their advantage.

In terms of the players on show at the 2018 FIFA World Cup, Japan’s Shinji Kagawa had been considered a real creative force throughout his career and amassed 31 goals and 20 assists in his 97 international appearances. In addition to Kagawa, the creative influence for this movement was further cemented at the tournament by Spain’s David Silva, Egypt’s Abdallah Said, Switzerland’s Blerim Džemaili and England’s Jesse Lingard, who all featured in the top ten but behind Kagawa’s impressive 45 offers in between per 90 minutes. The common denominator among these players was their position within their nation’s team shape, with each of them playing as an attacking midfielder in a 4-2-3-1 formation.

In to out

Not all movements to receive the ball start and end within the opposition team shape, which brings us nicely onto in-to-out movement. This occurs when a player makes a movement from inside the opposition team shape to outside the opposition team shape so as to receive the ball between the first and final opposition team unit. Not all football matches are played with both teams setting up with expansive and open shapes in which there is lots of space for players to operate and receive the ball between units. This is why in-to-out movement can be instrumental, particularly when the opposition condense the space between their units, meaning that the free space naturally occurs outside the opposition team shape. If a team is trying to play expansive football, a central midfielder may make this movement in order to encourage their own team’s full-backs to progress higher up the pitch, or an attacking midfielder playing inside the opposition team shape may make a movement to receive the ball in the space outside the opposition team shape.

An analysis of the 2018 FIFA World Cup showed that, once again, it was the more creative players that led the way in this type of movement. The Croatian attacking midfielder, Andrej Kramarić, offered the most in-to-out movements, with an average of ten per 90 minutes. This was closely followed by Japan’s attacking midfielder Shinji Kagawa, with 9.8. When we look at the phases of play in which Kramarić and Kagawa made the in-to-out movements, we start to see how they differ as players and gain a better understanding of their roles within their respective teams. Kagawa made 50% of his movements in the build-up phase, looking to move out to the left-hand side of the pitch in order to find space and provide an option for a line-breaking pass from one of his team-mates. Kramarić, on the other hand, only made 34% of his movements in the build-up, but 11% in the final third phase of play, indicating that he becomes more involved as the play enters the final third. This analysis offers us an improved insight into the different player profiles that exist and may enable us to draw conclusions about their effectiveness in the future.

Out to in

The opposite of in-to-out movement is out-to-in movement. This occurs when a player makes a movement from outside the opposition team shape to inside the opposition team shape so as to receive the ball between the first and final opposition team unit. This type of movement is predominantly made by wide players, such as full-backs or wide midfielders/wingers. An in-game example of this type of movement would be a wide player looking to move infield to receive a pass between the opposition’s midfield and defensive units. Another example would be a wide midfielder moving infield as a decoy movement to enable their own team’s full-backs to receive the ball higher up the pitch and create a more expansive attacking shape.

During the 2018 FIFA World Cup, nine of the top ten players who performed this movement played out wide for their respective nations. One of the icons of the modern game, the Brazilian maestro Neymar, ranked third with 7.8 out-to-in offers per 90 minutes. However, the top two places were held by players who are less known globally but renowned in their homelands, namely Saudi Arabia’s Salem Al Dawsari (9.1) and Switzerland’s Steven Zuber (8.1). Positionally, it was discovered that 70% of the top ten players who utilised the out-to-in movement to receive the ball were right-footed players operating on the left wing. This lends to the fact that they could come inside the opposition team shape to get on the ball with their lead foot, giving them a better angle to progress the ball forward and have a significant impact on their team’s attacking threat.

In behind

The final type of movement in focus for this article is in-behind movement, which is when a player makes a movement to receive the ball behind the opposition’s final unit. This type of movement is often made by the attacking players in the team, such as the centre-forwards, wide players and midfielders. It can be made anywhere on the pitch but tends to occur in the attacking half.

In-behind movement can improve a team’s performance and attacking output. The movement can be made by attackers to exploit the space behind a high defensive line, enabling them to receive a through-ball or lofted pass behind the defensive unit without any defenders hindering the route to goal. Repeatedly performing this movement can cause the opposition’s defensive line to drop deeper and therefore open the space between the opposition’s midfield and defensive units, allowing the creative players more space in which to receive the ball behind the midfield unit, with options ahead of the ball to play into.

When this movement is performed closer to the opposition’s goal, it is often in conjunction with a pass that breaks the opposition’s defensive line and results in an attempt on goal.

During the 2018 FIFA World Cup, Germany offered to receive the ball in behind a total of 159 times per 90 minutes, registering 40 more movements per 90 minutes than second-placed Australia. Out of the four teams that reached the semi-finals of the competition, only Belgium featured among the top-performing nations in this respect, ranking fifth overall, with 110 in-behind movements per 90 minutes. The eventual 2018 FIFA World Cup winners, France, ranked mid-table, in 19th place, which suggests that quality of movement is more important than the number of movements made.

Conclusion

Analysing the different types of movement to receive the ball offers a fascinating insight into how teams at the very highest level of the game look to get on the ball. This then allows us to start developing an idea of what movements we would expect to see from specific players or in specific positions on the pitch, and from this we can begin to understand the tactical reasoning behind such movements or the specific tactical advantages that can be gained by performing a certain movement to receive the ball. As this series progresses, we will delve deeper into this topic and start to focus on the types of movement in specific areas of the pitch and how each one can improve a player’s individual performance as well as the overall team performance.